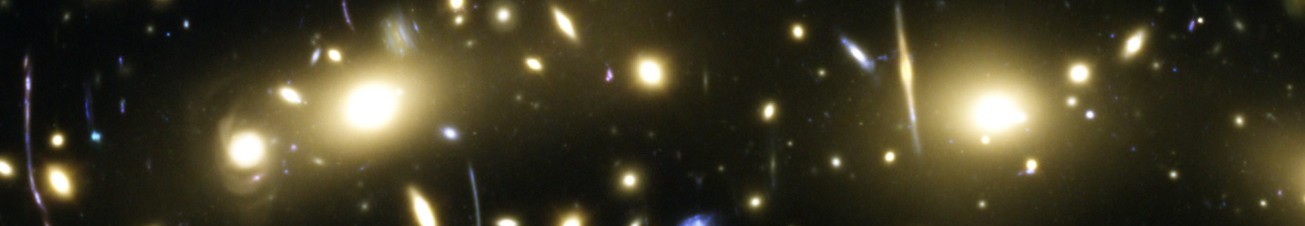

Monster stars are giant superluminous stars, tens of thousands or hundreds of thousands brighter than the Sun. Despite their superb luminosity, with the most powerfull telescopes they can only be seen in our Galaxy or in galaxies nearby. However, astronomers can rely on a trick offered by nature to see these stars much, much farther away. As predicted by general relativity, space can bend in the presence of very massive objects. Light traveling through that warped space bends as well, and can be focused into our telescopes in the same way a piece glass that is shaped into a lens can focus light into a focal point.

The most massive objects known capable of bending space are galaxy clusters, with masses up to thousands of times the mass of our own Galaxy. If a telescope points towards one of these massive galaxy clusters, objects that are very far away and right behind the cluster can be magnified, the same way a lens at the end of a telescope would magnify distant objects. The combined effect of a human made telescope looking through the natural telescope that is a galaxy cluster is similar to a larger telescope, hence allowing to see objects that are too faint to be observed directly without the aid of these natural telescopes. The magnification provided by these natural telescopes (galaxy clusters) is not uniform, and there is a very narrow region around the center of the galaxy cluster where the magnification factor can reach several thousands. These narrow regions are known as critical curves and objects that are observed near these curves are magnified by very large factors. With magnification factors ~1000 provided by these natural lenses, a telescope such as the JWST (with a mirror size of ~6 m) observing a star near a critical curve becomes the equivalent of a giant telescope with a mirror size of ~200 meters in diameter. That is, 20 times larger than the largest telescope on Earth (The Spanish GTC in the Canary Islands). With such giant telescopes, astronomers can see very luminous individual stars at very large distances, provided these stars happen to be observed close enough to a critical curve.

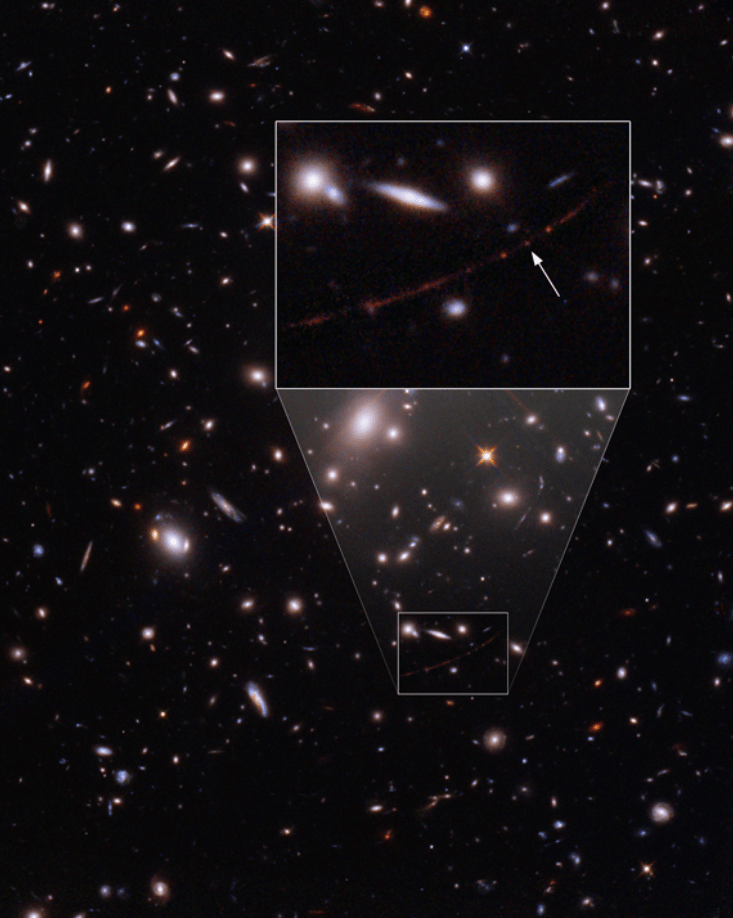

Several stars have been observed this way, and in previous posts we have discussed a few of them (Earendel, Godzilla). In a recent work, we present a new Kaiju star named Mothra, which is specially interesting because it can be used to study models of dark matter (DM), arguably, the most mysterious substance in the universe (with the permission of space itself). When observing lensed stars with very large magnification factors, we often see a double image of the star twice, one on each side of the critical curve but very close to it. One of the star has positive parity (that is, it represents a direct image of the true image), and the other has a negative parity (that is, it appears as a reflection of the true image). For stars, we can not directly observe the parity since we only measure their fluxes, and we can not resolve the star even with magnification factors of several thousands. However, the parity of the image can be easily established from a model of the galaxy cluster. In the case of Mothra, we only see one of the two expected images. This is not unusual for images that have positive parity, since images of stars with negative parity are often demagnifed by tiny lenses in the galaxy cluster. This tiny lenses are stars in the galaxy cluster that introduce small imprefections on the otherwise nearly perfectly smooth gravitational lens.

One of the first hints that something unusual was happening for Mothra is that the image we detect with our telescopes corresponds to the one with negative parity. The image with positive parity is not detected. Again, this is still possible for relatively short periods of time (months to a year) since images with negative parity can momentarily have large magnification factors. Howevere, for Mothra, the magnification has remained unusually large for at least 8 years, which is the time spanning since the first Hubble Space Telescope of this star in 2014, and the last observations of Mothra in 2022 made with the James Webb Space Telescope. Stars in the galaxy cluster (or microlenses) can not maintain large magnifications factors for this long period. A much more massive object (a millilens) is needed with a mass at least ten thousand times the mass of the Sun. This millilens needs to be close enough (in projection) to the detected image of Mothra in order to magnifiy it for at least 8 years. The image below shows a cartoon representation of what it is believed to be the configuration near Mothra.

The two blue ellipses represent the double (specular) image of the galaxy hosting the star Mothra. LS1 and LS1′ are the two expected images of Mothra. Only LS1 is clearly detected suggesting that some invisible massive object near LS1 is magnifiying the image of Mothra forming at LS1, but not the other image forming at LS1′ . The black dot represents the approximate position of the halo of DM needed in order to magnify Mothra for at least 8 years. This timescale sets the lower limit of this halo. Masses below 10000 times the mass of the Sun can not magnify LS1 to the required values for 8 years without fine tuning the relative velocities and direction of motion of Mothra. The two red dots represent an unresolved object in the host galaxy that is imaged twice at positions b and b’ (as expected in lensing). These two objects appear with similar brightness in the JWST images, indicating their magnification is not being perturbed by any small structures. This fact is used to set an upper limit on the dark matter halo. It is found that this halo must be at most 2.5 million times the mass of the Sun. Otherwise, the clump c’ would be fainter (demagnified), contradicting the observations. Hence the mass of the black object in the image above is between 10000 and 2.5 million times the mass of the Sun.

This constrain on the mass is used to study possible models of dark matter. One particular model, known as Warm Dark Matter (WDM) predicts that the DM particle is relatively light and moves very fast (almost at relativistic speeds). In this scenario, small structures can not form because the velocity of the DM particle is larger than the escape velocity of the small structure. There is a relation between the mass of the DM particle and the mass of the smallest halo that can exist in this model. From the constrain in the mass of the halo discussed above, astronomers found that models where the DM particle is lighter than 8 keV are in tension with the observations. This is one of the tightest constraints on this type of model coming from astrophysical probes. An alternative model of DM is tested with this observation. It is known as Fuzzy Dark Matter or FDM. In these models, the mass of the DM particle is incredibly small, in the range of 1E-22 eV. Such a small mass has a very large associated De Broglie wavelength (this determines the quantum size) in the astrophysical scale. Lighter masses have longer wavelengths and for very small masses, the wavelength is larger than the size of small galaxies. Since we observe small galaxies around us, this has been used in the past to set a lower limit on the mass of the DM particle for this particular model. From observations of Mothra, one can study the optimal mass range in which the observations would math the predictions from the FDM model. It was found that if the DM particle is in the range of 0.5e-22 eV to 5e-22 eV, the lensing perturbation from the FDM could explain the observations of Mothra (detection of LS1 and non-detection of LS1′). This mass range is interesting because it explains other issues that could be in tension with the standard cold dark matter model, such as the lack of cusps in dwarf galaxies or the possible defficit in the number of satellites around more massive galaxies. Some of these issues can be alleviated with non-exotic baryonic physics but the debate continues about these possible tensions with the standard model. More observations, similar to Mothra, will help in the near future to favor some models against others until we reach the point where only one model survives, or more interestingly, no known model is able to reproduce all observations simultaneously, demanding a new revolution in our understanding of the universe.